Key Findings:

· The four percent rule applied to a 60/40 stock fund/bond fund portfolio is not a good retirement plan.

· Under the four percent rule, the longevity of financial assets in retirement is not affected by initial asset levels. But the initial level of retirement wealth is an important determinant of financial security.

· A more realistic retirement plan would be based on the minimum amount needed to fund consumption after considering taxes, debt, and unanticipated expenditures.

· Retirement plans may have to be revised when portfolios experience large losses early in retirement, as was the case for the 60/40 stock fund/bond fund portfolio for people who started retirement in 2021.

· 2021 retirees who purchased bonds with specific maturity dates and Series I bonds fared better than retirees reliant on bond funds.

· Many simulations of the four percent rule failed to account for impact of fees.

· Higher spending rates early in retirement are often justified when retirees are delaying claiming Social Security benefits, converting traditional assets to Roth assets, or planning to downsize later in retirement.

Limitations of Retirement Plans Based on the Four Percent Rule

The starting point of many discussions of retirement planning is the four percent rule. The four percent rule stipulates that retirees can start retirement by spending four percent of financial assets per year and by adjusting annual distributions for inflation. The approach often assumes that retirees hold a 60/40 stock fund/bond fund portfolio.

This approach has many limitations and should not be the cornerstone of your financial plan.

Financial outcomes for a person strictly adhering to the four percent rule are unaffected by the initial amount saved for retirement, even though people with a larger amount of financial wealth are better prepared for retirement than people with less financial wealth. Under the four percent rule, the rate of financial asset depletion and the likelihood a person outlives her financial resources depends entirely on the rate of return on assets and the inflation rate.

· Consider two retirees strictly adhering to the four percent rule, one with $1,000,000 in financial assets and the other with $2,000,000 in financial assets. Under the four percent rule, the initial level of spending for the person with $1,000,000 in assets is $40,000 and the initial level of spending is $80,000 for a person with $2,000,000 in assets. The assets will be fully depleted in 25 years in both circumstances if the return on assets is equal to the inflation rate, the case when all assets are invested in an inflation linked bond. When the assets get a 6.0 percent return and the inflation rate is 4.0 percent the assets last around 33 ½ years.

The four percent rule does not consider whether a spending level of four percent is a suitable or adequate benchmark. In some cases, four percent of financial assets does not provide enough resources in retirement while in other cases four percent of assets provides more than the person plans to consume.

An alternative approach would base disbursements in retirement on some ratio of disbursements to the federal poverty line or a percent of pre-retirement income. Under this type of assumption, the person with a larger amount of financial assets is better off than a person with fewer assets.

· Consider a retirement plan that calls for distributing 3.0 times the federal poverty line or $45,180, adjusted for inflation. Under an assumption of 6.0 percent returns and 4.0 inflation assets would last slightly more than 94 years if initial assets are $2,000,000 and a bit more than 28 years if the person has $1,000,000 in assets. The person with $1,000,000 in financial assets is already consuming more than four percent of his or her resources and would more quickly deplete her resources by increasing initial disbursements from $40,000 to $45,180.

Household spending is impacted by unexpected events and expenditures and in some periods the retired household will be forced to spend and distribute more funds than planned. The likelihood of unexpected expenditures is another reason for having a larger level of retirement savings.

The four percent rule does not consider how debt and taxes impact required financial savings and the adequacy of financial resources in retirement.

A person with a mortgage or consumer debt, will need to disburse additional funds to maintain the same lifestyle as the person without a mortgage. A person with a fully taxed conventional retirement account will need to disburse more funds to maintain the same lifestyle as the person with financial resources in an untaxed Roth account.

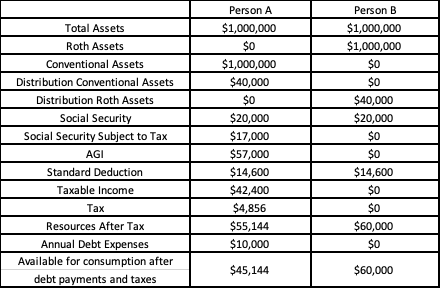

Consider two people both with $1,000,000 in financial assets and with $20,000 in Security benefits, both distributing four percent of financial assets ($40,000) from a retirement account. Person A has $10,000 in debt and all financial assets in a conventional retirement account. Person B has $40,000 no debt and $40,000 in a retirement account.

Person B will have a better lifestyle and has substantially more resources for consumption after taxes and housing expenses than person A for three reasons. Person B has no housing expenses, the Roth distribution is not taxed, and the Social Security benefit is not taxed because Roth distributions are not included in modified adjusted gross income.

Person B with no debt and a Roth could cut distributions by $14,856 ($60,000 - $45,144) and have the same amount for consumption after debt payments and taxes as person A who has mortgage debt and a conventional retirement account.

The previous research on the viability of the four percent rule including Bengen (1984)

Fink, Pfau, and Blanchett (2013), and Spitzer, Strieter and Singh (2007) used simulations and average price per asset class. These papers did not consider fees charged by retirement plan managers and funds.

A median-wage worker in a high-cost 401(k) plan can pay more than $100,000 in fees over the life of the worker. These fees are not explicitly considered in simulations or empirical projections of the adequacy of retirement wealth. A discussion of ways to minimize the impact of 401(k) fees can be found here.

Retirement planners considering the adequacy of retirement savings and the appropriate distribution level need to consider the impact of fees.

Empirical assessments of the adequacy of retirement savings, understate the impact of large losses at the beginning of retirement if asset prices initially fall and inflation rises. A new retiree in 2021 holding wealth in FBALX a fund that holds around 35 percent bonds and 65 percent stock would not have fared well.

· The fund fell from around $31 per share in early 2021 to $22 per share later in 2021 and is just now returning to around $30 per share. Cumulative inflation would have increased benefits by around 18 percent between 2021 and 2024.

Most financial advisors try to prevent their clients from making matters worse during a downturn. Good Luck to the financial advisor attempting to calm this client.

Most financial simulations of the adequacy of retirement income, including the trajectory of wealth under the four percent rule assume the retiree has invested in the overall stock market and the overall bond market. Many households choose other investments.

The 2021 to 2024 period was not a good time to hold a 60/40 equity fund/fixed income fund portfolio because initially both stock funds and bond funds fell in value. Retirees who purchased bonds or bond ladders with specific maturity dates could have spent funds from maturing bonds without taking a capital loss.

A retiree holding a share of financial wealth in Series I savings bond would also be better insulated from financial volatility at the beginning of retirement because as discussed here Series I bonds never fall in value and can be used to fund consumption when other assets do lose value.

Financial wealth will be more volatile for people invested in individual equities than for people invested in the overall market. The level of financial assets and the type of investments both impact the ability of a retired household to withstand financial turmoil without cutting expenditures.

The decision to delay Social Security benefits and the decision to convert conventional retirement assets to Roth assets can increase future after tax income. The strategy of delaying claims to Social Security benefits and converting conventional assets to Roth assets generally requires households spend a larger percent of retirement assets early in retirement. Go here for more details.

A future house downsizing will decrease future costs and increase future financial assets. It is often reasonable to incur additional costs on housing and spend a larger share of financial assets before freeing up additional cash by downsizing to a less expensive home. The decision to downsize and when to downsize is difficult both because of the emotion surrounding leaving a long term residence and the fact the home is the largest portion of most people’s wealth. The factors affecting the downsizing decision are discussed here.

There is no one-size-fits-all rule for how much to save in retirement. A rule based on the premise that one should initially spend four percent of assets and adjust this spending level for inflation is not going to work well for a lot of people.

A more appropriate retirement planning framework would be based on the minimum amount a person would need to spend in retirement. Required initial distributions would account for likely tax obligations and debt payments. Simulations of the adequacy of retirement savings would test for unexpected random expenditures and volatility in financial markets.