Roth IRAs as an Inflation Hedge in a World of Frozen Social Security Tax Thresholds

How Unindexed Benefit Tax Rules Amplify Inflation’s Bite — and Why Even Modest Roth Balances Can Help

How Unindexed Benefit Tax Rules Amplify Inflation’s Bite — and Why Even Modest Roth Balances Can Help

Inflation doesn’t just raise prices. Social Security taxation thresholds have remained fixed since the 1980s resulting in higher taxes on Social Security benefits even when real benefits are unchanged. Case studies of a single and married couple retirees reveals even a 10% Roth allocation meaningfully reduces both direct and indirect taxes, preserving spendable income in an inflationary environment. The results underscore Roth accounts’ underappreciated role as an inflation hedge in a non-indexed tax system.

Abstract

This paper examines how Roth IRAs can serve as a hedge against the growing tax burden created by the non-indexation of Social Security benefit taxation thresholds. Because these thresholds have remained fixed in nominal dollars since the 1980s, inflation gradually exposes a larger share of benefits to federal income tax, even when real income is unchanged. The analysis here is an evaluation of the benefits of having a relatively small portion of retirement assets in a Roth account in an inflationary environment for a single individual and a married couple. The results show that even modest Roth allocations reduce both direct taxes on withdrawals and indirect taxes on Social Security benefits, providing a persistent advantage that widens over time, especially in an inflationary environment.

Introduction

For many retirees, the taxation of Social Security benefits depends on income thresholds that have remained unchanged for decades. While the cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) to Social Security benefits partially offsets inflation, the income thresholds that determine how much of those benefits are taxable are fixed in nominal terms. As a result, even moderate inflation gradually pushes more retirees into higher taxable ranges, increasing the share of their Social Security that is subject to federal income tax.

This paper explores how Roth IRAs can serve as a partial hedge against this “tax bracket creep” caused by unindexed Social Security taxation rules. Because qualified Roth withdrawals are not included in adjusted gross income or in the calculation of provisional income, a retiree who draws part of their income from Roth sources can reduce both their direct tax liability and the amount of Social Security subject to tax.

Two case studies illustrate these effects over time:

A single retiree comparing a fully traditional portfolio versus a mix of traditional and Roth accounts.

A married couple filing jointly facing similar conditions.

Case Study One: Single Individual

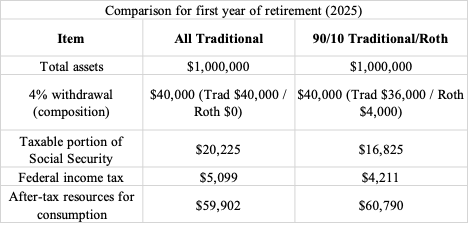

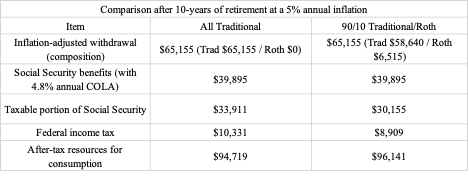

This scenario models a single retiree with $1,000,000 in total retirement assets and $25,000 in initial annual Social Security benefits. The retiree withdraws 4% of total assets each year, with withdrawals and benefits adjusted for inflation. The analysis assumes a steady 5.0% annual inflation rate and a 4.8% annual increase in Social Security benefits over time. All calculations use 2025 federal tax rules, including a $15,750 standard deduction and fixed Social Security taxation thresholds ($25,000 and $34,000).

In the first year, the Roth component saves the retiree roughly $888 in federal income tax—about half from lower taxable withdrawals and half from reduced taxation of Social Security benefits. The 90/10 mix yields approximately 1.5 percent more disposable income in the first year.

By year ten, the unindexed thresholds cause nearly the maximum 85 percent of Social Security benefits to become taxable. The retiree with partial Roth income still pays $1,422 less in taxes—$780 from the tax-free Roth withdrawal itself and $642 from reduced Social Security taxation.

Inflation magnifies the difference between the two income sources: as nominal income rises, the Roth portion prevents further “tax creep,” preserving roughly $1,400 more in annual spendable income.

A modest Roth allocation in a retirement portfolio can offset part of the increase tax stemming from a Social Security rule, which does not adjust for inflation.

Case Study Two: Married Couple

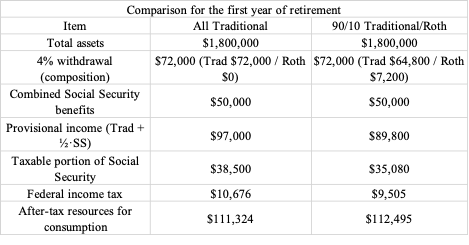

This second scenario models a married couple filing jointly with $1,800,000 in total retirement assets and combined annual Social Security benefits of $50,000 ($25,000 each). As in the prior case, the couple withdraws 4 percent of total assets in the first year, with withdrawals and Social Security adjusted over time for inflation. The same 5.0 percent annual inflation rate and 4.8 percent annual Social Security COLA are assumed, and all calculations use 2025 federal tax rules.

Thresholds for Social Security taxation for married filers remain fixed at $32,000 and $44,000—unchanged since 1984—so rising nominal income gradually exposes more benefits to tax. The 2025 standard deduction for a married couple filing jointly is set at $31,500.

Decomposition of tax savings:

Direct savings from smaller taxable withdrawals: about $864

Indirect savings from reduced taxable Social Security: about $307

Combined tax savings: $1,171

The Roth mix raises first-year spendable income by roughly 1 percent on the same total assets.

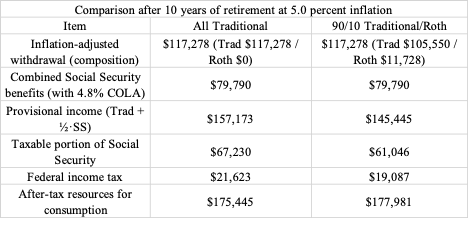

Decomposition of tax savings:

Direct savings from shifting $11,728 to tax-free Roth withdrawals: about $1,405

Indirect savings from lower provisional income and reduced taxable Social Security: about $1,131

Combined annual savings: $2,536

The Roth share thus produces roughly $2,500 more in after-tax spending after ten years, or about 1.4 percent more real income on the same inflation-adjusted withdrawals.

Interpretation

This married-couple scenario reinforces the central conclusion:

Because Social Security taxation thresholds are nominal, inflation steadily pushes a greater portion of benefits into the taxable range even though real purchasing power does not increase.

The higher-income couple hits the 85 percent taxable limit quickly, but the Roth component still meaningfully lowers their tax exposure.

Over a decade, the Roth share consistently cushions inflation’s impact on total taxes, maintaining greater after-tax income without altering withdrawal rates or investment returns.

Conclusion

The two case studies highlight how Roth accounts can mitigate the long-term tax consequences of unindexed Social Security taxation. Both single and married retirees experience rising effective tax rates as inflation pushes nominal income above static thresholds, causing a growing share of benefits to be taxed. Even a modest Roth allocation—10 percent in these examples—reduces both direct taxes on withdrawals and indirect taxes on Social Security benefits by lowering provisional income.

For the single retiree, annual tax savings rose from about $900 in the first year to roughly $1,400 after a decade of inflation. For the married couple, tax savings increased from just over $1,100 initially to about $2,500 by year ten. These results show that Roth income provides a compounding advantage over time as inflation interacts with fixed tax thresholds.

The broader policy implication is clear: in a world where Social Security taxation is not indexed to inflation, Roth accounts serve not only as a hedge against future tax-rate uncertainty but also as a structural defense against inflation-induced tax creep. Even modest Roth balances can sustain higher after-tax income and slow the erosion of real retirement purchasing power over time.

This analysis focused on the static benefits of modest Roth allocations under persistent inflation. Future work will examine behavioral and portfolio implications — such as how Roth holdings can allow retirees to distribute less while maintaining equal after-tax income, or how dynamic withdrawal strategies can further mitigate “tax creep.” I’ll also explore policy scenarios where indexing Social Security taxation thresholds would alter the comparative advantage of Roth accounts.

Authors Note: This analysis of Roth as an inflation hedge is offered as a free note. If you’d like to support this work — and receive premium posts, working drafts, and early access to new analyses — I’m offering two introductory options:

· 🎓 Six months free for new paid subscribers

· 💡 50% off an annual membership (only $30 total)

Paid subscribers receive a steady stream of research-driven writing on personal finance, health insurance, retirement strategy, and the stock market. Your support makes it possible to continue and expand this kind of work.