Shifting Catastrophic Health Costs to Medicaid

Why Socializing the Costliest Medical Cases Could Cut Private Insurance Premiums by 15–25 Percent

Abstract

Health care expenditures in the United States are heavily skewed, with a small proportion of individuals responsible for the majority of total spending. This concentration of risk inflates private insurance premiums and complicates efficient risk pooling. This analysis examines a hybrid model in which Medicaid assumes responsibility for catastrophic individual expenditures above $50,000 per year, leaving private insurers to cover expenditures between a $5,000 deductible and that threshold. Using recent Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) data, the analysis estimates that such a shift could reduce private insurance premiums by approximately 15–25 percent for the working-age population. The findings align closely with results from earlier simulation models of partial reinsurance, suggesting stability in the shape of the health expenditure distribution and confirming the potential of public catastrophic pooling as a premium-stabilization mechanism. More broadly, the results illustrate why policies that lower insurance prices directly can outperform approaches that rely on increasingly large income-based premium subsidies.

1. Introduction

The concentration of health spending among a small subset of individuals poses a persistent challenge to private insurance markets in the United States. A tiny fraction of enrollees generates the majority of total medical costs, resulting in high premiums, adverse selection, and instability in private risk pools.

This analysis explores a hybrid policy design under which the public sector—specifically, Medicaid—functions as a catastrophic insurer, assuming responsibility for medical spending above $50,000 per enrollee per year. Private insurers would continue to cover spending between a $5,000 deductible and that threshold. While Medicaid is typically discussed as a coverage program for particular populations, it already functions implicitly as a payer of last resort for extremely high-cost cases. This framework makes that role explicit and system-wide.

The core question is how much such a policy would reduce private insurance premiums, given the empirical distribution of health expenditures. Using recent Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) data, the analysis estimates the expected change in insurer liability and, by extension, in premiums.

This work updates and extends earlier research (Bernstein, 2010), which used a micro-simulation of public reinsurance to study similar mechanisms. Despite differences in method and scope, the estimated effects on premiums are remarkably similar, underscoring the persistence of catastrophic cost concentration in U.S. health care.

2. Background and Related Literature

A broad literature documents the extreme skewness of health expenditures. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality reports that the top 1 percent of spenders account for roughly 22–24 percent of all spending, while the top 5 percent account for about half. This long tail drives much of the premium burden in private insurance markets.

Previous policy analyses have examined government-sponsored reinsurance as a corrective mechanism. Cutler (1994) and Blumberg and Holahan (2008) proposed public subsidies for catastrophic claims to stabilize private markets. Bernstein (2010) modeled a public reinsurance system covering 80 percent of claims above $50,000 and estimated average premium reductions of 15–18 percent.

This analysis builds on those foundations by examining a structural hybrid model: instead of partial public co-insurance, Medicaid would act as the payer of last resort for catastrophic cases, fully absorbing costs above a fixed threshold.

3. Analytical Framework

Let X denote an individual’s annual medical expenditure and let d denote the deductible, set at $5,000.

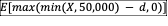

Under a fully private insurance plan, the insurer’s expected liability is the average amount of spending above the deductible, with negative values set to zero:

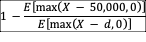

Under the proposed hybrid system, where Medicaid covers all spending above $50,000, the private insurer’s expected liability becomes the average amount of spending between the deductible and the catastrophic threshold:

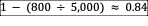

Assuming actuarially fair pricing, the proportional change in premiums is given by the reduction in expected insurer liability. Written explicitly, the proportional premium reduction is:

This expression represents the fraction of private insurance premiums eliminated when catastrophic expenditures are shifted from private insurers to Medicaid.

4. Data and Parameterization

The analysis uses data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component for 2018–2022, supplemented by AHRQ Statistical Brief #556.

Key empirical benchmarks for the working-age population (ages 18–64) include:

• 99th percentile of annual spending: $80,990

• 95th percentile of annual spending: $30,206

• Mean spending among the top 1 percent: $147,071

• Share of total expenditures above $50,000: approximately 10–12 percent

Based on these figures, only about 1–3 percent of privately insured individuals exceed the $50,000 threshold in any given year.

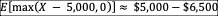

To approximate expected post-deductible expenditures:

5. Results

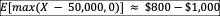

Substituting these empirical values yields a premium ratio of roughly:

Thus, premiums under the hybrid plan would be approximately 16 percent lower than under a fully private plan with the same deductible. Across plausible parameter ranges, the reduction falls between 15 and 25 percent.

At the population level—approximately 160 million privately insured individuals—this corresponds to a transfer of roughly $130–190 billion annually in catastrophic costs from private insurers to Medicaid.

6. Fiscal and Policy Implications

This reallocation would reduce volatility in private insurance premiums and lower average costs for employers and individuals, but it would increase federal and state Medicaid expenditures.

Because Medicaid pays lower provider reimbursement rates than private insurance, the net fiscal impact could be smaller than the gross transfer of liabilities, depending on case mix and cost-control mechanisms.

From a distributional perspective:

• Employers and workers would benefit from lower premiums

• State and federal budgets would bear higher catastrophic costs

• Risk pooling would become more stable across the population

7. Comparison to Bernstein (2010)

The earlier study (Bernstein, 2010, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance) simulated partial public reinsurance covering 80 percent of spending above $50,000 using 1999–2006 MEPS microdata. That work estimated premium reductions of 15–18 percent for privately insured populations.

The current analysis differs in three key respects:

• Full coverage versus co-insurance: Medicaid assumes 100 percent of costs above $50,000

• Analytical transparency: the approach replaces simulation with a closed-form expression

• Updated data and scope: the analysis uses 2018–2022 MEPS data and covers the entire working-age private insurance population

Despite these differences, the quantitative results are nearly identical, suggesting a stable health-expenditure distribution and reinforcing the robustness of catastrophic reinsurance mechanisms.

8. Discussion

The findings confirm that the upper tail of the health-expenditure distribution continues to exert disproportionate influence on private insurance costs. Transferring catastrophic risk to Medicaid would smooth premiums without altering the underlying efficiency of routine medical care delivery.

The approach parallels international models in which public insurance absorbs catastrophic costs while private insurers manage routine risks. Implementation in the United States would require coordination across state and federal Medicaid systems, clear eligibility triggers, and safeguards against adverse provider incentives.

9. Limitations and Future Work

Several caveats apply:

• MEPS underreports extreme outliers due to top-coding; commercial claims data suggest even heavier tails

• The model is static and does not incorporate behavioral responses or provider-payment effects

• Fiscal outcomes depend on Medicaid reimbursement policies and cost-containment rules

Future work should integrate survey and administrative claims data to estimate fiscal exposure more precisely and examine dynamic responses to catastrophic reinsurance.

10. Conclusion

Both analytical and simulation-based evidence indicate that transferring catastrophic claims above $50,000 from private insurers to Medicaid would reduce private insurance premiums by roughly one-fifth while modestly increasing public expenditures.

These results reinforce the case for catastrophic reinsurance as a powerful tool for stabilizing insurance markets. By aligning current estimates with those from earlier work, the analysis highlights the durability of U.S. health-spending concentration and supports renewed consideration of public catastrophic coverage as part of health-system reform.

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Statistical Brief #556.

Bernstein, D. (2010). Health Care Reinsurance and Insurance Reform in the United States. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance, 35(4), 588–607.

Blumberg, L., and Holahan, J. (2008). Public Reinsurance: Stabilizing Markets While Protecting Families. Urban Institute.

Cutler, D. (1994). Market Failure in Health Insurance. NBER Working Paper No. 6769.

Health Care Cost Institute. Health Care Cost and Utilization Reports, 2018–2022.

Kaiser Family Foundation. How Concentrated Are Health Care Expenditures?

Milliman. U.S. Stop-Loss Market Survey Reports.